- 848.932.7474

- info@rutgersalumni.org

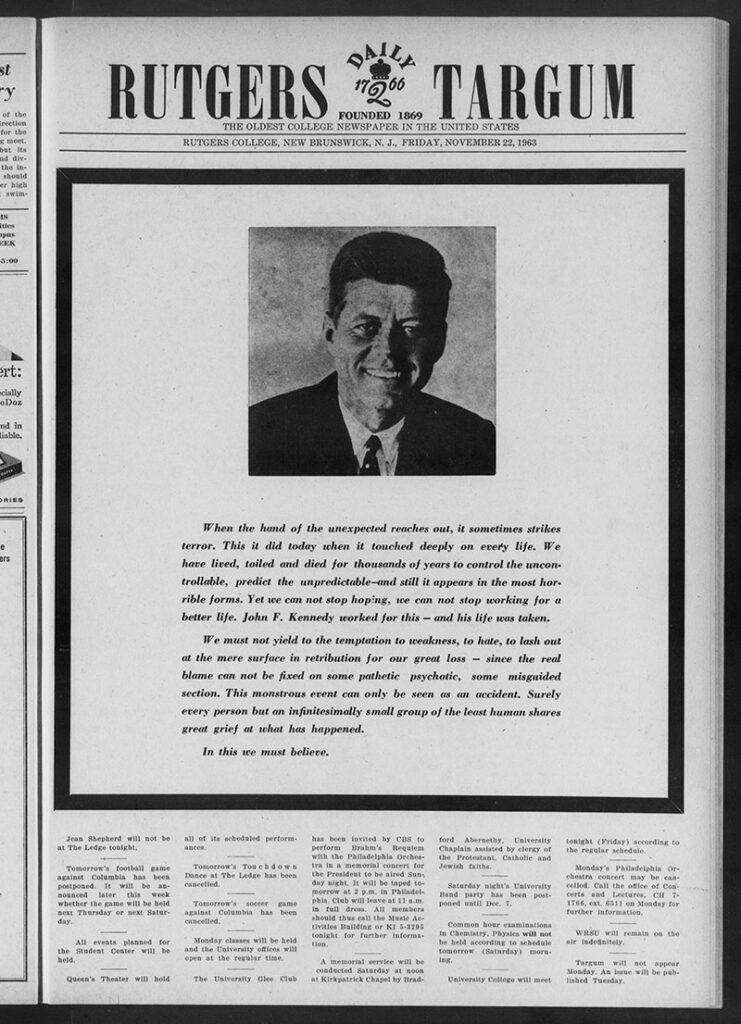

November 22, 2023, will mark the 60th anniversary of the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy. It’s one of those events where individuals who lived through it remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news.

Two Rutgers alumni shared their and other students’ recollections about the atmosphere on campus that day and in the days that followed.

By Hal Shill RC’66 and Larry Benjamin RC‘66

It began as a normal Friday afternoon in late November. Students were attending their last classes of the week. The weekend promised a season-ending football game with Columbia and a concert by radio-TV humorist Jean Shepherd. Parties were being planned at fraternities (at that time Rutgers only had a male student population). Some students were looking forward to events on campus, while others were planning to go home for the weekend or catch up with coursework. Thanksgiving break was just five days away.

Then everything changed. President John F. Kennedy was shot in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963, at approximately 1:30 p.m. EST. He was pronounced dead at about 2 p.m. News reports trickled out slowly at first in that pre-Internet world. By mid-afternoon, the news had spread quickly, mostly by radio. Rutgers President Mason Gross closed the university. The football game and Shepherd concert were postponed. Most weekend plans were altered or canceled altogether.

The events of that day would be etched indelibly in the minds of every Rutgers student. Even 60 years later, the memories of that day—how and where we learned about the assassination, what we did afterward, how the nation responded, how it shattered our beliefs—remained sharp.

Back in November 2013, 21 members of the Rutgers Class of 1966 shared their recollections of that tragic day. Their accounts were subsequently published in that class’s 50th reunion yearbook . Excerpts from those historic “class memories” are shared below, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the event.

Word of the tragedy spread quickly. Some students heard it directly on the radio. Others learned about it from classmates. Many observed a palpable gloom on the campus, with radios turned on, classes cancelled, and professors and classmates alike in tears.

Jack Greene was in a surveying field class. The news came across on a transistor radio carried by a fellow student. “At first,” Jack reported, ”we thought it was a sick joke, like Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds,’” but we started switching stations and found the same report on all stations. We walked the mile back to the civil engineering building where, by now, the TVs were all turned on and everyone was numb with depression.”

Charles Repka was in an electrical engineering review session “when someone burst through the door and told us, ‘some nut down in Dallas has just shot the president!’”

While walking to class, Bill Roberts “heard someone yell from one of the frat houses that Kennedy had been shot.” When he reached his class, “the professor came in crying and announced that class was canceled.”

The late John Bravo was in a physics lab when “a guy appeared at the doorway with a transistor radio at his ear and, with a dramatic flair, switched off the radio and said, ‘That’s it…President Kennedy has been assassinated!’” As John recalled, “The word ‘assassinated’ seemed so foreign.”

At WRSU, the college radio station, the late Rich Hersh was in the midst of his afternoon music show when the United Press International warning bells began ringing, meaning that important news had occurred. Six bells rang, signifying a very significant event. Multiple lines said, “Switching to Dallas” and “Please take it, Dallas.” Hersh then received a call from the Mutual Broadcasting System asking if he would go to Washington. On the way back to his dorm, he saw “one of my professors sitting on a bench…crying uncontrollably.”

Bill Lewers (RC’65) felt upbeat after surviving an advanced calculus test. As he entered his dorm floor, however, “something seemed a bit strange. Most of the dorm room doors were open and there seemed to be radios on everywhere.” It did not seem normal, so Bill asked one of the students:

“Is something going on?”

The student responded by saying simply, “Kennedy’s dead.”

Bill Pollinger and Walt Parquet heard the news while picking up dry cleaning at a laundry on Easton Avenue. Back on campus, they told students getting out of class what had happened. As Bill recalled, “No one would believe us and gave us strange looks as if we were pulling a prank. Later, he said, “People started coming out of the College Avenue dorms in a daze. Many were just sitting on curbs, staring out into space, and continued to sit there all night.”

Walking back to his dorm from a canceled physical geography lab, Bill Kover “encountered groups of girls from St. Peter’s High School dressed in Catholic uniforms. Some were in tears. It all seemed surreal. There were more young girls in tears at the bus station. The ride home on the bus was in total silence. I think everyone was in shock. When I arrived home, my mother broke down in tears.”

Many Rutgers students felt compelled to respond. Michael Perlin, Leo Ribuffo, and a contingent from Zeta Beta Tau fraternity, among others, went to Washington for the funeral. Many also attended a memorial service in Kirkpatrick Chapel. Others went home. Some students took even more active measures.

Ted Robb and the Rutgers Choir performed Brahms’ “Requiem” with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra as a memorial tribute to JFK. Their performance at Philadelphia’s Academy of Music was broadcast live nationwide on CBS television.

As requested by the Mutual Broadcasting System, Hersh flew to Washington to cover Kennedy’s funeral. The network had a plane ticket waiting for him at Newark Airport.

Perlin, a Daily Targum reporter, called the office of Rep. Ed Patten, the Congressman whose district included Rutgers, for a statement. He then worked with fellow Targum staffers to organize a memorial edition of the newspaper. Needing to do more, he then went to WRSU, where he had worked as a freshman, and taped an interview with Patten before heading to Washington for the funeral.

Presidential assassinations had been episodes learned in American history classes, not something imaginable in the early 1960s.

After processing the event, many Rutgers students wondered about the short-term and long-term implications of the assassination. While the prevalent reaction was that a lone “nut case” had done it, some wondered whether a foreign nation was involved. Kover wondered whether it would lead to World War III.

Presidential succession was a more immediate concern. Lewers heard rumors that Vice-President Lyndon Johnson had suffered a heart attack. If he were disabled, who would lead the nation?

Policy concerns also surfaced. If Johnson became president, would he continue the limited civil rights initiatives of the Kennedy Administration? Would our foreign policies change? Would hostile foreign actors, specifically the Soviet Union or Cuba, take advantage of uncertainty in Washington?

It was “business as usual” for a few students. Hal Shill observed a touch football game outside the river dorms that afternoon. “How,” he wondered, “could students be playing football at a time of national crisis?”

The national cross-country championship was scheduled for Monday, November 25, in Ann Arbor, Mich. Coach Les Wallack, his wife, and seven cross-country runners piled into a Volkswagen mini-bus for that 614-mile trip on Saturday. After “a long, quiet drive,” Paul Hetzel remembered, the meet was postponed until Tuesday. The runners “lay around in a motel watching the 24-hour coverage. All of a sudden, we see (accused assassin Lee Harvey) Oswald being brought out and Jack Ruby shooting him, live on the screen.”

Bravo heard yelling in the TV room of his Alpha Chi Rho fraternity house. He stepped into the room, where a fraternity brother immediately told him, “Some guy shot Oswald! Right in front of the TV cameras!”

Like many fellow students who had gone home, Ray Kaden watched events unfold throughout the weekend. He viewed the shooting of Oswald live in an underground garage, thinking, “How can this be happening? What kind of security do they have in Texas?”

Greene recalled thinking that “Oswald got what he deserved,” a sentiment shared by many others.

Kennedy’s flag-draped casket was moved from the White House to the Capitol rotunda on November 24. Many Rutgers students were among the 250,000 individuals who filed past it to pay their respects. The funeral took place on Monday, November 25. Rutgers students were again among the thousands lining Pennsylvania Avenue in respectful silence as his casket was taken to St. Matthew’s Cathedral for the funeral.

Others watched at home on TV. Robb remembered “world leaders walking out of the White House, Richard Cardinal Cushing presiding with his Boston-accented Latin, and the muffled drums – the muffled drums – a sound that I will always remember.” As he further recalled, “There was a feeling of profound sadness.”

The Kennedy assassination was a turning point for Rutgers students and the entire nation. His aging but well-liked predecessor, Dwight David Eisenhower, had suffered four heart attacks during two terms in office.

In contrast, Kennedy was a youthful, vigorous president with a gift for inspirational rhetoric, an agent of generational change with a strong appeal for college students. His popular approval rating averaged 70 percent during his abbreviated term of office

As Kaden put it, “He seemed to bring a new spirit of optimism to Washington.”

For Greene, “Things changed after Kennedy was killed. A candle was blown out.”

As Pollinger noted, “An entire generation of collegians would realize that the world wasn’t just a place to hang out and have fun and wait for the next party. Life was tough and for us, with Vietnam on the horizon, was going to get a lot tougher.”

Shill recalled that “the initial shock and uncertainty would gradually be supplanted by a sense that the country would survive, albeit without a leader whose rhetoric had inspired many of us and had led us through the Cuban Missile Crisis without a nuclear war.”

For Larry Benjamin, “it was the event that helped define our generation. Our belief in ‘Camelot’ was shattered. The hope that it inspired was gone. Vietnam and the drug culture, Watergate and gasoline lines were about to come.”

When classes resumed on November 26, Lewers’ American government class discussed the implications of the assassination. In his words, “While we were all comforted by the resiliency of the American political system to withstand such a tragedy, we also felt a sense of vulnerability in the succession law as it existed.”

Ironically, Benjamin’s political science class had discussed presidential succession just a few hours before the assassination. Those discussions anticipated the 25th Amendment, which allowed the president to select a new vice president with Congressional approval.

Americans have occasionally been traumatized by generational events that seemed inconceivable before they occurred. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 terrorist attacks stunned the nation and altered assumptions about national security. For Rutgers students in the 1960s, the JFK assassination was that belief-shattering event, an abrupt end to a popular presidency, the closure of an age of youthful innocence, and a prelude to the political violence of coming years.

Footnotes

Authors

Hal Shill is Class Historian, Rutgers Class of 1966

Larry Benjamin is Class Correspondent, Rutgers Class of 1966